Conflict is an essential and defining part of liberal democracy, so when does conflict turn into something more? To ground this question, we look to democratic theory, and more specifically, what democracy requires. Fundamentally, liberal democracies need basic democratic trust. That is, everyone involved in the political domain is playing the game by the rules. Political polarisation starts to creep in when this basic trust begins to fracture. This is when political actors transgress and disregard basic democratic rules. We might recognise this when the political discourse descends into some kind of chaos and crosses the bounds of democracy.

The term polarisation has become problematic in the public discourse because any form of political conflict is called polarisation and deemed dangerous to democracy. Political science scholars like Sartori (1966) and Schedler (2023) defined polarisation as a dynamic, self-feeding process centred around the breakdown of democratic trust. This can occur when bad political actors or non-democratic politicians dismantle any type of accountability and oppress fundamental rights. Polarisation can also happen within good democratic states, too, when political actors destroy democratic trust in a flippant manner and in bad faith, much like when former US President Donald Trump said the 2020 US election, which he lost, was rigged.

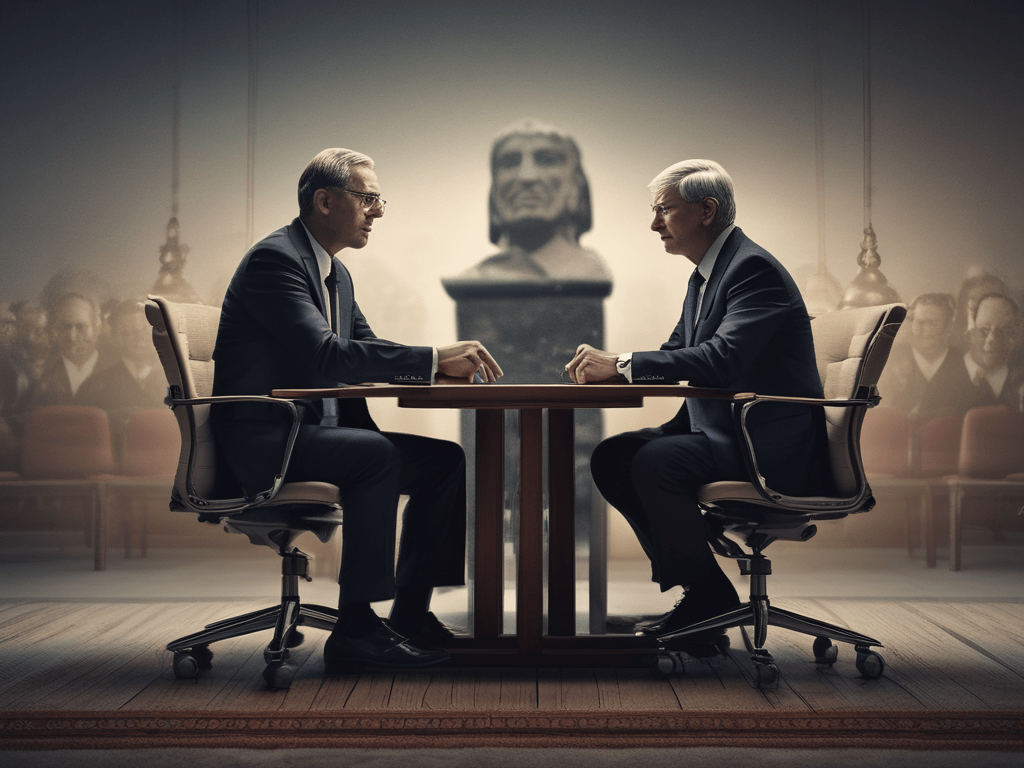

Democratic politicians need to identify polarisation and call out anti-democratic actors. This might be harder today with an increasing number of two-party systems. Political parties in democratic countries are now mainly categorised into two dominant parties. Earlier, particularly in Europe, there were centre parties and parties on the left and right, with the centre as the dominant party. Today, it is not unusual to see two poles or two parties competing against each other, which means the centre has disappeared. This makes it hard for any conciliatory actors or parties to situate themselves seamlessly within the political dynamics. So, what we’re left with are two political parties competing for power, raising the stakes and no middle ground. With more than 50 elections this year, it will be a defining time to gauge how polarised the world is.